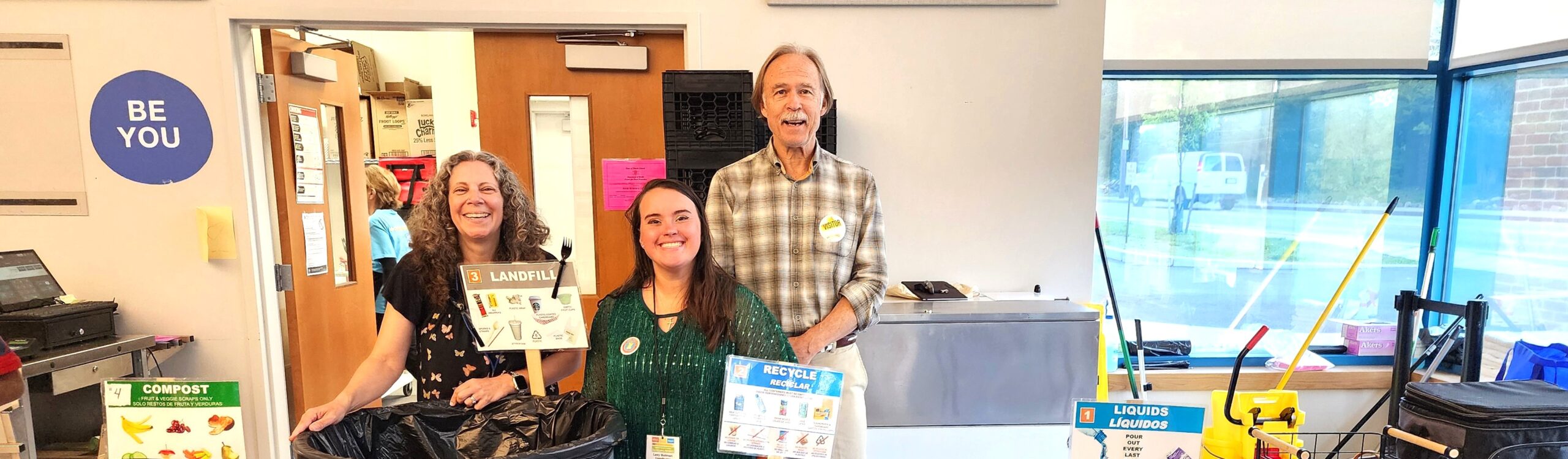

The ‘food waste’ stations in the cafeteria of Garvin Elementary School in Cumberland were set up by the RI School Recycling Project. Left to right are Kendra Gay, Lexy Bulman, and Co-Director Jim Corwin. (Photo by Julia Steiny/Rhode Island Current)

When kids take a lunch break, they also help their own community thanks to the RI School Recycling Project

When lunch winds down at Garvin Elementary School in Cumberland, the kids take their trays to the food recycling line. They sort their lunch detritus into well-marked bins and buckets. A fifth grade “food waste ranger” oversees the process, monitoring what goes into which container to avoid contaminating the contents.

The line starts at a table for food that could be redistributed — unopened milk cartons, power bars, wrapped cheese sticks — and a basket for intact fruit and vegetables. If kids are still hungry, they can pick up something extra there thanks to support from the RI School Recycling Project. Every one of the 52 schools that participated in the program last year received a refrigerator to store perishables. That food is distributed to hungry students and food insecure families, who are about 30% of Rhode Island’s population. (School staff who are close to the families stock backpacks for those they know need help.)

Next, students move past the waste-collection station which has a bucket for pouring leftover liquids, along with a bin marked “recycle” with pictures of what can be recycled, and another for trash that can’t go anywhere but the Central Landfill in Johnston, like plastic bags and straws. The last stop collects food scraps — apple cores and banana peels that will go to the school’s commercial composting partner. A few schools make their own compost.

On the day I visited Garvin at the end of May, it was “zero waste” day, so kids were especially jazzed because a completely empty, sorted tray earned them a sticker and maybe a prize, like a T-shirt.

Lest this seems like a cool but small stakes school activity, consider this:

In the 2023-2024 school year, preliminary data from 42 of the participating schools shows that more than 227 tons of food waste was diverted. Each school does its own waste audit.

According to Anthesis Global: One ton of Co2 is equivalent to the electricity consumption of 0.65 average households for a year. Driving a gasoline car for 5,000 miles. Taking 72 high-speed train trips of 300 miles each. 2.6 round-trip flights between New York and Miami. Rescuing Leftover Cuisine says that 227 tons is the equivalent of 35,000 meals.

More than greenhouse gases, though, the kids focus on Rhode Island’s one and only landfill run by the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation (RIRRC). A 2015 report warned that the landfill was filling so quickly, it would close in 2038. For the record, Connecticut’s landfills are already full, so the state sends about 40% of their solid waste to Ohio or Pennsylvania at a cost of just under $100 million a year. Rhode Island could be in the same boat in the not-too-distant future.

Since that report came out a decade ago, efforts including this one by the RI School Recycling Project have bought the state more time, extending the state landfill’s closure date to 2045.

In response to pleas from the quasi-public agency that operates the landfill, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a law in 2014 banning food waste, but with caveats.. Unfortunately, the law was another toothless unfunded mandate, like much of education legislation. But partner agencies and philanthropies generously stepped in to fund the RI School Recycling Project.

Back in Garvin’s lunchroom, the vigilant food-waste fifth grader minding the stations, told me his interest was “To keep the landfill from filling up.”

“This way we can stay here and not put a landfill in our town,” he added.

Of course, Cumberland is under no such threat. But the project pays for second-year student rangers to take a field trip to the top of the garbage mountain where they gape at its impressive quantity. The Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation education staff teach students about the realities of mindlessly tossing solid waste. (You can take that tour too.)

The corporation developed a curriculum for young people about methane, its toxic effects, and about greenhouse gasses in general. Students learn that on any given school day in Rhode Island, just under 28,000 pounds of compostable food goes into the landfill. Of that, 4,000 pounds is food that is perfectly fine and could be redistributed. Tiny Rhode Island’s public schools generate 5 million pounds of food waste a year.

Teachers adapt curricula to build on what students are learning from this real life experience, including having the kids collect the data to calculate the waste audit.

Furthermore, the project saves money. Redirecting the recyclables reduces the number of dumpsters the school needs, along with the tipping fees for the landfill. Warren Heyman, the project’s operations director, said a Warwick school was putting a dozen bags of trash a day into its dumpster.

“On the first day we implemented our program, the school only took out two bags of trash, around 10 pounds,” Heyman said. “That’s 50 fewer bags a week. That’s one less full dumpster of trash a week.”

Granting agencies are so enthused about this work, they’ve recently given enough money to bring on another 50 schools in the new school year that begins Tuesday in Cumberland for first through ninth grade students. All grades are in session Wednesday.

The money pays for the skeletal, part-time staff of two, Co-Director Jim Corwin, and Heyman, plus stipends for volunteers. The project welcomes volunteers to help them double their reach.

Training sessions for interested volunteers began last week.To learn more, contact Heyman by filling out the contact form on the project’s website.

The project offers educational materials and techniques to help schools get started and stay active. Also covered are the fridges, field trips, containers, prizes and the fees for composting companies to take the food scraps. (See available companies on page 15 of this presentation.)

After a well-deserved rest, Corwin and Heyman had a super busy summer. They’ve got their hands full, but they dearly hope grocery stores and restaurants catch the recycling bug.

If the kids can do it, so can they.

First published: RI Current News, September 1, 2025

Feel free to post comments about Julia’s work at juliasteiny.com